Gaines made Blunt earn his scholarship, but it didn’t take long for the young veteran coach to figure out he had something special on his hands. There isn’t a lot of film from Blunt’s career in the early-to-mid 1960s, but archived sports clips from those who saw him live tell the story of a ‘dazzling playmaker” who “thrilled the crowds with his passing and dribbling.”

The Rams were coming off back-to-back CIAA Championships behind Cleo Hill in 1960 and ’61, having gone on to beat John McLendon’s powerful Tennessee State teams in the NAIA Tournament before falling in the quarterfinals. Add in the loss of two other starters and a key reserve and Gaines told the media he was hoping just to slide into the CIAA Tournament in eighth place (only the top eight teams made it back then when the league comprised most of what is now the MEAC as well as current teams.)

Like many coaches of his era, Gaines didn’t believe in giving freshmen too much playing time. But he apparently saw something in Blunt that convinced him to give the young Philadelphian a chance. As a result, the Rams won the CIAA regular-season title and Blunt became one of the first freshmen to make the All-CIAA team.

“When he saw me, he saw a point guard that could pretty much help and guide a ball team to success. And so he allowed me the opportunity to dictate what had to occur on the basketball court once the game started.

And that’s exactly what he did.

‘Some of the ball players on the team didn’t like it, but if they didn’t do what I told them to do, they never got the basketball,” Blunt said matter-of-factly.

The CIAA was populated with talented players at the time thanks to two things– segregation and the point-shaving scandal of the 1950s.

“It was incredible. Nobody wanted to be involved with black kids anymore,” Gaines told the Baltimore Sun’s Jerry Bembry in 1993. “If you’ve ever been to a trout farm, you know how the stream flows down to the mountain and when the fish come up you can almost reach out and grab them. That’s how easy recruiting was in those days. There was no place for this talent to run, and they started coming here.

“I had a chance to play against some of the real good athletes that would have never made it had it not been for black schools,” Blunt said.

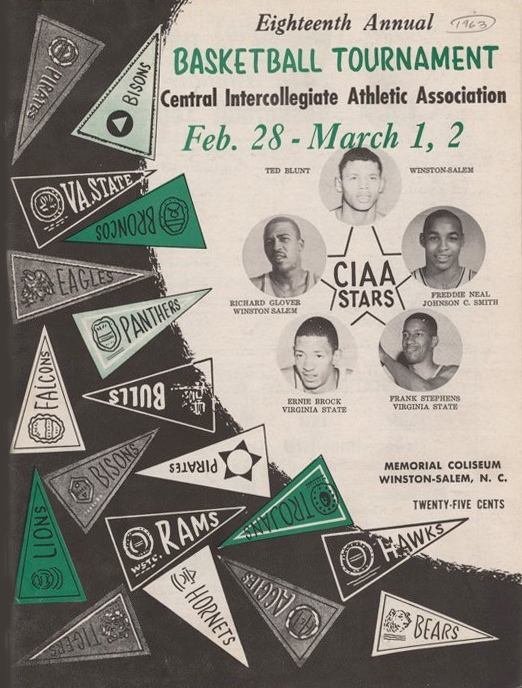

One of those athletes was a young man from Greensboro named Fred Neal. The world would later know him as Curly Neal. Blunt remembers him as a sharpshooting guard on rival Johnson C. Smith.

“Curly was never known to be a dribbler,” Blunt said. “Curly Neal was a shooter. Curly Neal could stop on a dime and hit a two-pointer or a three-pointer.”

“Curly was considered one of the finest shooters around. Steph Curry that plays for the Golden State Warriors– that’s how good a shooter he was at that time. I would equate him to that level.”

Indeed, Blunt’s knack for ballhandling and quarterbacking the Rams offense was acknowledged by the sports scribes in the 1960s.

Blunt is acknowledged as the smoothest playmaker and court magician of the CIAA. Blunt’s slight of hand is not restricted to his dribbling. He leaves opposing guards open mouthed in wonder when he passes the ball. “One moment Blunt has the ball in his hands then phoof, it’s gone and some other Ram has it.

“The CAROLINIAN”

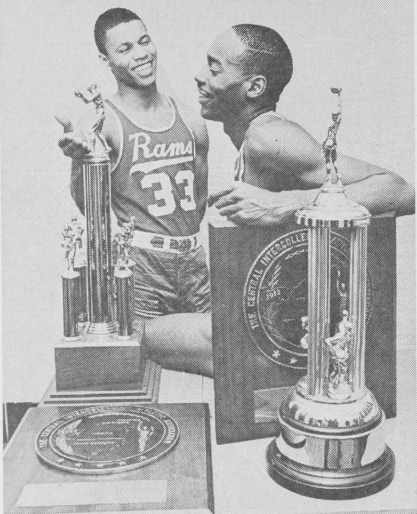

The Rams would win the CIAA Tournament in Blunt’s sophomore season, 1962-63, and Blunt was named the tournament’s Most Valuable Player. Forty years before the “And I Mixtapes” made millennials go crazy, Teddy Blunt and his teammates played a brand of ball that was so good that even racism couldn’t keep people away.

“People would show up to see our games, six, seven, thousand people in the (Winston-Salem) Coliseum,” Blunt said. “Comprised of both white, black and brown people. Which was unheard of at the time in the South, but they showed up to see good basketball games and Coach Gaines was able to get the Coliseum for us five, six, seven times a year.”

Those bigger venues were needed by then as the TC Rams (Teacher’s College) matchups against Johnson C. Smith, North Carolina Central, Virginia Union and Norfolk State were must-see action in an era where, unless you were there, you could only read about it in the paper or hear it on the radio.

Blunt remembers the most heated rival, though, was North Carolina A&T. The two schools were separated by about 30 miles, and the two coaches – Gaines and A&T’s Cal Irvin– had been teammates at Morgan State University in the 1940s. Blunt remembers the games being intense, physical and sometimes bloody. Particularly a matchup in Greensboro in which his teammate Richard “Juice” Glover was giving an A&T player named Irvin Mulcare the business.

“Mulcare said if you score another basket, I’m gonna bite you in the head. Glover scored this basket, and we’re running down the court, and Mulcare is running down the court with blood dripping from his mouth. And there’s Juice Glover with a big hole in his head. And we had to rush him to the hospital to get a tetanus shot.”

[postBannerAd]