The Black College Football Hall of Fame announced its latest class of inductees on Thursday, honoring four legendary players, one Hall of Fame coach and a conference commissioner. It was another stellar class, and while some may debate who was picked over whom, no doubt all these gentlemen have made their contributions to black college football.

That being said, there were many reactions and debates once the class was announced that had nothing to do with the actual inductees. They had to do with the Hall itself.

[inArticle]

For some reason there are people in the world (or at least on the internet) who suggest they do not understand the reason that there is a Black College Football Hall of Fame. While the natural inclination is to conclude that anyone who makes this argument simply chooses to ignore historical fact and prefers endless online debate with anything that celebrates blackness uniquely, let’s assume someone blind to the facts literally does not understand why the Hall or HBCUs themselves exist.

A Century of Exclusion

College football is celebrating its 150th year in 2019. For basically the first 100 years, college football was lily white across much of the East Coast, literally all of the South, and a good part of the Southwest. That means that pretty much all of what is currently made up of Power Five football was totally in-accessible for black athletes regardless of talent level.

ACC football was integrated by Maryland’s Darrell Hill in 1963. The SEC, which has made billions off the unpaid labor of black student-athletes, didn’t start to put black players on the football field until 1967. The University of Texas finally brought in Julius Whitter in 1970, one year after fielding the last all-white national championship team.

That’s less than 50 years that the shackles of Jim Crow were effectively loosed from college football. Barred from football teams, just as they were from white colleges, young black men went where they were welcomed and began to build their own version of college football. Biddle students traveled from Charlotte to Salisbury, North Carolina to play Livingstone and Black College Football was born.

Over the following decades, black talent poured into these schools from all over in order to get an education, with football serving as a much-needed diversion from the vicious systematic racism which kept them out of larger state schools reserved for the “superior race.” The NCAA was formed in 1905, but black colleges were not welcomed by the new regulating body. In 1912 the Colored Intercollegiate Atheltic Association was formed to help HBCUs on the East Coast organize, and over the next decade the SIAC and SWAC helped spread the movement west.

College-aged men went to die on battlefields of Europe for Old Glory during World War I, while they were unable to go to school or play football at schools like Alabama, Texas, Florida and other universities. Instead, they returned home and matriculated to schools like Lincoln, Hampton, Tuskegee and Prairie View. As the 1920s dawned and pro football became a reality, black men were blackballed from the league for most of its first three decades, which meant that no matter what a black man accomplished on a football field, college football was his ceiling.

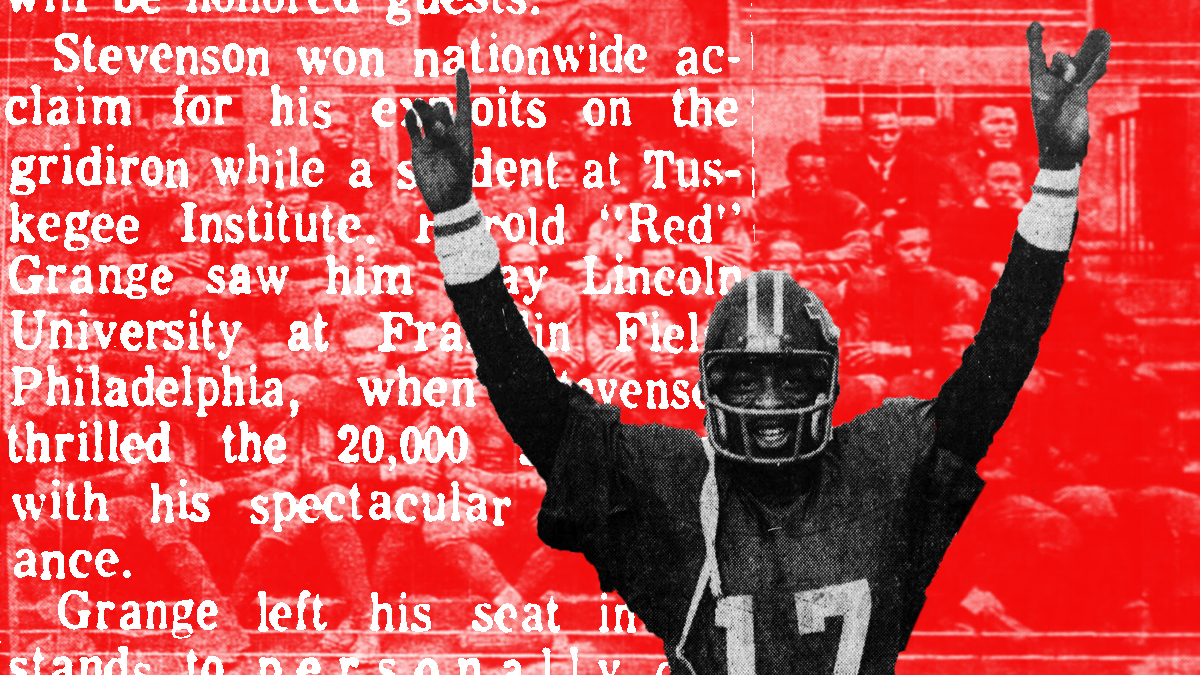

Save for a few schools on the West Coast or midwest, black student-athletes had zero avenue to play collegiate football outside of black colleges. Legendary players like Jazz Byrd, Ben Stevenson and others became legends in the black press, but were virtually ignored by mainstream media. Imagine Ezekiel Elliot or Lamar Jackson competing for their entire careers without any mainstream media coverage and with no chance of playing professional football. Their stories and feats would only live in the eyes of the people who watched them, and eventually be lost to time.

There are several generations of black college football players, most of them long since gone from this earth, that didn’t have to imagine that fate; they lived it.

Eventually, pro football opened its doors to black college players once schools like Grambling, Florida A&M and Morgan State began pumping out players that kicked ass against those in the “power conferences.” Add in a persistent civil rights movement and suddenly schools that would not allow blacks to do anything other than pick up trash in their stadiums were clamoring for the talent that once pulsated at HBCUs.

HBCUs were never created to push black supremecy but were created to give descendants of formerly enslaved-people opportunities to better themselves. HBCU football is an extension of that legacy which remains a vital part of the African-American fabric. And while black athletes and students in general can attend any school they want, HBCUs and the Black College Football Hall of Fame exist to push forward as well as celebrate our rich history. And that history doesn’t get swept into the closet just because the capitalism of college athletics demanded more black bodies.

The irony of this faux debate over whether or not there should be a Black College Football Hall of Fame will most assuredly take an interesting term later this month when it is announced that a Caucasian quarterback, FAMU’s Ryan Stanley, is a finalist for the organization’s player of the year award. Because, despite its name, black college football has had white student-athletes for decades as HBCUs have continued to be inclusive despite being created out of exclusion.

Even with the establishment of the BCFHOF, many pioneers like Jazz Byrd, A.W. Mumford and others have yet to take their rightful place in the hall. The stories and legacies of these men who are no longer alive still matter and the story of black college football, or college football period, is not complete without them.

The BCFHOF isn’t perfect, but it is very necessary.

[inArticle]