The NCAA has been dealt yet another blow by the courts as it ruled that Vanderbilt quarterback Diego Pavia should be eligible to compete another season. This after spending seasons at New Mexico State and Vanderbilt. Citing the recent NIL opportunities, the entire scope of NCAA eligibility has been turned on its side. With the free flow of the transfer portal and this new ruling, players wanting to go from high school and play directly with a four-year college will undoubtedly find it much more difficult. Pavia’s contention that he should be eligible follows a long line of defeats for the NCAA in maintaining its rule over college athletics. The new ruling opens the door for student-athletes to play two years of junior college (JUCO) football and still be eligible for a full four years at a four-year institution.

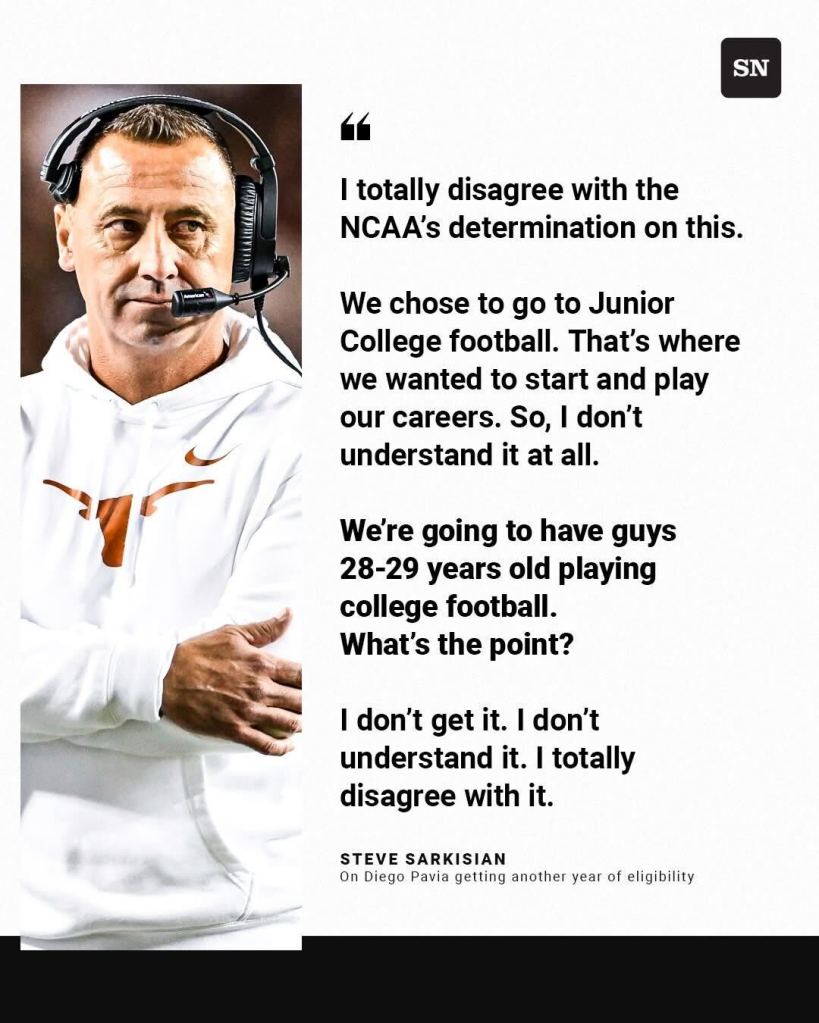

Essentially, with all of the exceptions the NCAA has already granted, it could lead to players in college football being 24 or 25 years old. If that athlete is granted a redshirt at any time, that could shoot up to 26 or 27 years old after playing two free seasons of JUCO football.

Judge ruled decision using U.S. Labor Laws

Chief U.S., District Court Judge William Campbell, Jr. returned his ruling and based it on labor laws, comparing the NIL abilities of student-athletes to general individuals entering the labor market. He called the NCAA bylaws “too restrictive.” This aligns with Pavia’s allegation that the restrictive law violated antitrust laws.

The NCAA, which has been battered with seemingly a continuous stream of lawsuits released the following statement after the ruling: “The NCAA is disappointed in today’s ruling and wants all student-athletes to maximize their name, image and likeness potential without depriving future student-athletes of opportunities. Altering the enforcement of rules overwhelmingly supported by NCAA member schools makes a shifting environment even more unsettled.”

Pavia played two years in JUCO and three years in FBS football. He started at New Mexico State in FBS and transferred to Vanderbilt. He has had success during his collegiate career. While at New Mexico State, he led his team to a defeat of Auburn. This season while under center for Vanderbilt, they defeated the University of Alabama which was followed by the much-publicized miles-long trek of the goalpost to the Cumberland River.

With the advent of the transfer portal, oversight is diminished

With the advent of the unbridled transfer portal, which was consented to after several lawsuits against the NCAA and more threatened lawsuits, spaces on NCAA Division I and Division II teams have shrunk. Opportunities have become more sparse as successful players as well as highly-touted players who are disgruntled have played musical chairs over the last few seasons. With little restriction, players end up playing for two, three, and even four different teams.

In the “win now” era of college athletics, coaches are leaning toward JUCO players with college experience as opposed to anyone who is not the absolute top tier of high school prospects. High school coaches have been telling good high school players who may be below that upper echelon to take offers literally as they come. That includes accepting D-II and D-II offers. The ultimate goal is to get the players in college with assistance to complete their educations and the landscape has completely flipped from even a few years ago.

Some of this has been fueled by the NCAA’s ease in a sweeping “COVID year” ruling, allowing players who played in 2020 to secure another year of eligibility. The swiftness in which that was instituted along with the irresponsible rollout of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) has left the NCAA looking like the old Wild West.

This is the third ruling in the last year that has gone against the NCAA. With the Power Four conferences set on establishing many of their own rules, this is further diminishing the authority of the NCAA. Some have pondered how long the NCAA would continue to exist and their relevance. This rash of decisions countering their efforts is a harsh reality. One of the NCAA’s longest and foremost rules they have enforced is the five-years-to-play-four. If this ruling stands, that benchmark premise of control by the NCAA will be all but neutralized.