Last year we took a look at the rise and climax of Indianapolis’ famed Circle City Classic. That story, “The Life of A Classic,” can be found here. Now we look at how changing demographics, an over-saturated market and the economy of college football altered the classic.

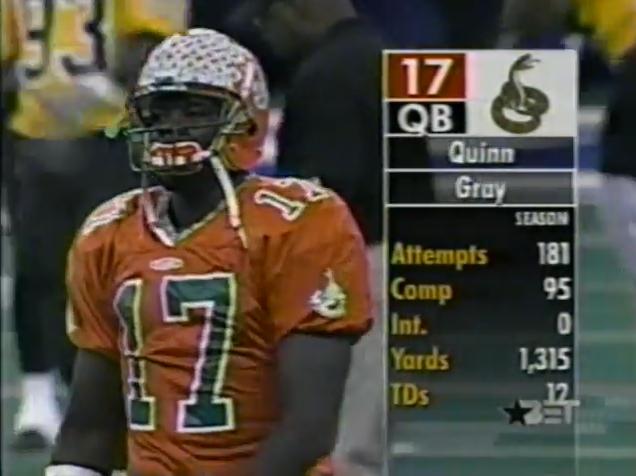

The Circle City Classic’s second decade saw more great battles on the turf of the RCA Dome. There was the infamous 1996 game where FAMU eeked out a 59-58 win over Hampton in not one, not two, not three, but six overtimes. The game lasted five hours and was played in front of more than 62k fans.

The next year, North Carolina A&T and Tennessee State combined for 86 points as better than 59k filed into the dome. Bethune-Cookman and Howard, the two teams that will meet in the 2018 game, showed up for the 1998 classic. That year Howard, led by All-American quarterback Ted White, beat Bethune-Cookman 32-25.

The classic continued rolling into “The 9-9 and 2000s” with powerhouse programs like Hampton and Southern, FAMU and Grambling State, etc, complete with a “Back That Thang Up” party in 2000. But change was on the horizon as changing priorities and financial realities, unforeseen at the time, would become big problems for the event that brought HBCU culture to the Midwest.

Death and demographics demand change

Rev. Charles Williams, the man credited with fueling the classic from its inception, died after a battle with prostate cancer during the Indiana Black Expo’s Summer Celebration. Williams inherited an organization in 1983 that was in debt, and 20 years later, had assets in excess of $2 million and annual revenues of nearly $6 million.

Williams’ death at 56 was a turning point for the Circle City Classic. The game, by now in its third decade, was starting to be a victim of its own success as well as changing demographics that didn’t favor it. The 2006 game had an attendance of just over 31k fans. By the time Florida A&M and Winston-Salem State showed up in 2007, attendance had started to dip as the game was becoming an afterthought to younger alumni and fans.

“There is a feeling among some that the focus has gotten off the game and that the game benefits African-American education,” local radio personality Amos Brown told The Star in 2007. “I think that has gotten lost in the shuffle in an emphasis on partying and entertainment that is part of the weekend.”

To their credit, classic organizers were trying to reach out to the younger generation. They were early adopters of social media, marketing on MySpace to reach the “YouTube Generation” as well as sending out e-mail blasts. But year-by-year attendance started to fade, as did the economic impact.

All About The Benjamins

As usual, it all boils down to economics. For the Circle City Classic, that has been true on several fronts. During the classic’s first three decades in the 1980s and especially the 1990s, fans poured into the game not just from Indiana, but from all over the Midwest to what was a one-of-a-kind event at the time. As the classic grew other cities in the Midwest like Detroit and Cleveland wanted to get in on the action, and began hosting their own classics. That cut the need to travel to Indianapolis, especially as the economy took a dive during the George W. Bush era.

During the classic’s heyday in the 1990s, payouts routinely hit six figures as the game was flush with sponsors. In addition to Coca-Cola’s quarter-million contribution (according to the Indianapolis Star in 1993), advertisers were paying anywhere from $8,000-$75,000 to appear in the downtown parade as late as 2000. By 2009 the game’s advertising revenue had declined 12 percent along with a 19 percent decline in attendance, according to the Indianapolis Business Journal.

[inArticle]

The game’s misfortunes came at a time when FBS teams were willing to give marquee programs like Grambling State, Southern and FAMU greater payouts for guaranteed games (Money Games, or simply Cut The Check games, around these parts). Playing in a MEAC vs. SWAC contest or against Tennessee State may have made for a more compelling game than getting beaten by the neighborhood FBS team, but with the classic struggling to find its footing, the Circle City Classic couldn’t count on the big names to come to town and fill up its stadiums as it had in the past.

Larger schools fade away

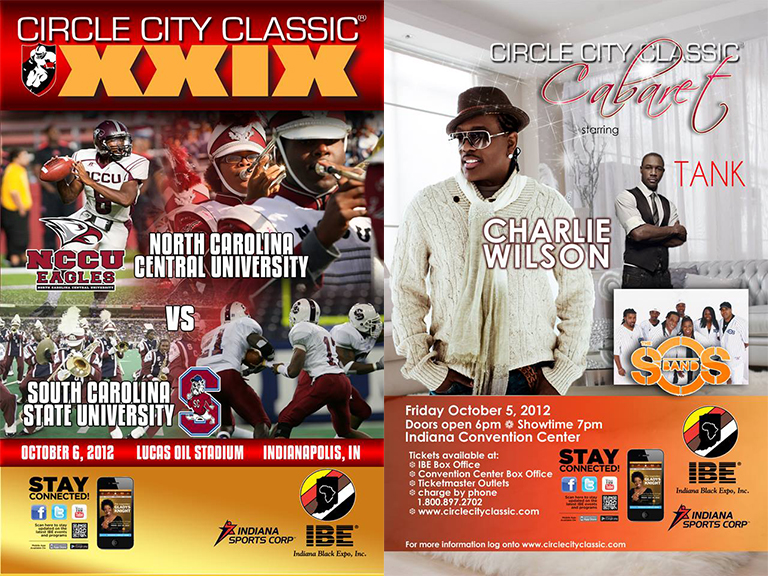

The 2012 game between North Carolina Central and South Carolina State drew just 18k fans in the dome. The following year a SWAC matchup between Grambling and Alcorn State drew just 22k fans. The following couple of years were a static matchup of two nearby HBCUs who both play in the SIAC; Kentucky State and Central State. The game has drawn between 15k-22k in those four seasons while fanbases of the bigger schools wonder why their schools are not among those invited.

“The best teams know who they are, and they charge accordingly,” Brown said in 2009. “It’s a challenge, but we’ve got to find a way to get it done to bring some excitement back to the event.”

[inArticle]

Can we get ’em back? (The good old days)

The 2018 classic will featured two FCS teams, an all-MEAC matchup of Howard and Bethune-Cookman, twenty years after the teams had a midwest showdown in the RCA Dome. It was shown on the ESPN platform, live via stream and then again on ESPNU via tape delay.

With all those changes in demographics, exposure and economics, its questionable whether the Circle City Classic can get back to the good old days of Levert (RIP Gerald) performing with the South Carolina State Marching 101 with a dome full of people back in 1993. Hopefully, though, bigger names and a national audience will be enough to pump new enthusiasm into this once-vibrant expression of black excellence.

Great read…