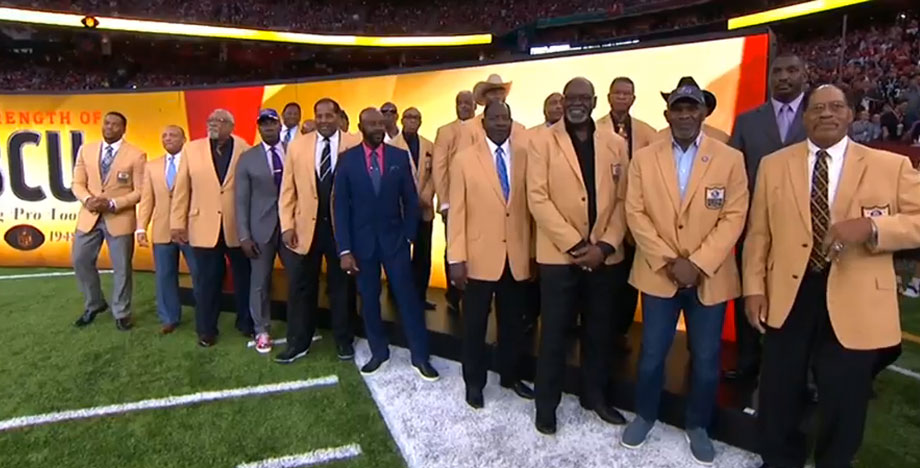

The NFL made a big splash this weekend during its’ Super Bowl LI pregame show when it gave a tip of the hat to HBCUs, by honoring Hall of Fame players who attended them. Players like Willie Davis (Grambling), Willie Lanier (Morgan State) and Mel Blount (Southern) were honored as well as more recent greats like Jerry Rice (Mississippi Valley State) and Shannon Sharpe.

This wasn’t a suprise, as it was announced in December ahead of the Celebration Bowl. Still, it was a nice nod to the contributions that players from HBCUs, and by extension the institutions themselves, made to makin the league what it is.

As great as the gesture was, the NFL can certainly stand to do more. Here are three things the NFL can do to expand on what was done Sunday night.

1) Extend its off-the-field careers program to all HBCUs

Last spring the NFL announced it would be creating a program to increase opportunities for off-the-field employment for products of HBCUs. That deal, however, only applies to the schools in the MEAC and SWAC, which represent just a portion of all HBCUs. It’s a nice start, but surely there are qualified candidates at HBCUs in the SIAC and CIAA, as well as HBCUs that compete in the NAIA.

We live in an athletic world that prioritizes big schools over small schools, and I get that. But many of the schools that have produced some of the biggest names in sports off the field have come from these other conferences. ESPN’s Bomani Jones went to Clark Atlanta, which is in the SIAC. Stephen A. Smith went to Winston-Salem State, which competes in the CIAA. As stated in “All HBCU Conferences Matter,“ the two oldest conferences shouldn’t be left out of opportunities just because they aren’t Division I.

2) HBCU-specific philanthropy

In recent years, the NFL has invited former players to come back and be a part of the NFL Draft by announcing selections. Every year there are more ex-pros announcing players being selected than current players getting picked in the NFL Draft. While giving a nod to the history of HBCUs in producing pros, it’s quite clear that the talent buffet that these schools once enjoyed have now turned into table scraps at best.

This isn’t the NFL’s problem, per se, but the league could do something to help. Resources at even the largest HBCU athletic programs are much less than recruiting budgets at many FBS schools. Since it is quite clear that players from HBCUs have helped the NFL turn into the financial juggarnaut that it is today, it would be great to see the league re-invest into the athletic departments that are hoping to produce the next round of NFL greats.

Of course the NCAA might have something to say to that, but even if they can’t directly send the money to athletic departments, at least they could make a financial contribution to the institutions themselves. Even a small (for the NFL) gift of $250,000 would go a long way for many schools.

3) Formally apologize for banning black players, or ignoring HBCU athletes in the first place

This one isn’t HBCU specific, but HBCUs were adversely affected. From 1933 through 1945, the NFL’s “Gentleman’s Agreement” amounted to a ban of black players in the league. And even before then, players from historically black colleges and universities were shut out of the league. Even after the NFL began to slowly integrate following World War II, no HBCU star would set foot on the field until Grambling’s Paul “Tank” Younger was finally given a shot by the Los Angeles Rams in 1949.

When we think in terms of black college football stars, we tend to think things started back with Eddie Robinson at Grambling or Jake Gaither at Florida A&M. The fact is there were several generations of great players that campe before them that have virtually faded into oblivion or are currently confined simply confined to a box in the attic of some black newspaper.

Players like Lincoln’s Jazz Byrd, Hampton’s Ed “Red” Dabney, Alabama State’s Oran “Duck” Frazier and hundreds of other names should be just as well known as Red Grange, Sammy Baugh and others, but lack of pro careers to validate them as well as mainstream press coverage have buried their legacies for far too long.

Sure, an apology itself won’t make all of that go away overnight. But that, along with the other things mentioned above, would show a longer-term commitment to paying back the schools that helped nurture the men that helped make the game what it is today.

One thought on “Three ways the NFL can continue to honor, support HBCUs”