It was in this setting that the legend of Jazz Byrd was born. This Pittsburgh Courier account waxes poetically about Byrd’s abilities as an open-field runner.

“The story of the 1922 and the 1923 games is an account of the individual achievements of a boy from the hills of Pennsylvania, “Jazz'” Byrd. who by rising to superhuman heights snatched victory for his team from certain defeat by virtue of long runs at critical moments in the former, his 65-yard dash gave his teammates a lead which they held throughout the struggle. Lincoln won. 13 to 12. Again, in 1923, after the “Bisons” had thrown consternation into the ranks of the “Lions”by a march down the field to a touchdown, this human antelope received a kickoff and galloped 90 yards, to Howard’s five-yard line before being chased out of bounds.”

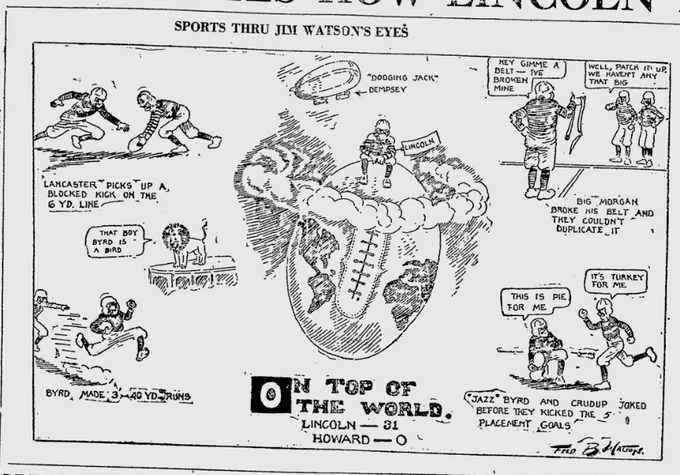

Byrd’s exploits came to a head in Washington D.C. at Griffin Field against Howard on Nov. 27, 1924. The game was to be Byrd’s last in a Lincoln uniform, and after two years of awe-stopping performances, fans were eager to see if he could do it again. The Pittsburgh Courier’s Bill Nunn wrote eloquently of the pomp-and-circumstance surrounding the game.”

“air of enthusiasm and excitement pervading the very heart of things…the flash and flare of college enthusiasm is manifest in all quarters of the historic old city…. All is expectancy; all savors of the feverish pleasure of witnessing a fair struggle on the football grid…. The hotels are filled.”

When the dust settled, Lincoln came away with a 7-0 win over Howard, its third-straight in the biggest black college football game of the year. Afterward, Lincoln coach U.S. Young gave his star player the highest praise.

“Byrd came, Byrd saw, and Byrd conquered. He is the ideal open field runner. Until I see “Red” Grange, of Illinois in action, I shall rate Byrd as the best open field runner in the country, black or white,” Young wrote.

The two-time All-American went on to coach and serve as athletic director at FAMU before returning to New York and becoming one of the first Black IRS auditors. He pushed for Lincoln to return to football after it disbanded the program, which it eventually did, but not until after his death in 1994.

An Unrecognized Legacy

Despite universal high praise from all that watched him in person, time has not been kind to the legacy of Jazz Byrd. You won’t find him in the College Football Hall of Fame, the Black College Football Hall of Fame, the CIAA Hall of Fame, or even the Lincoln Hall of Fame.

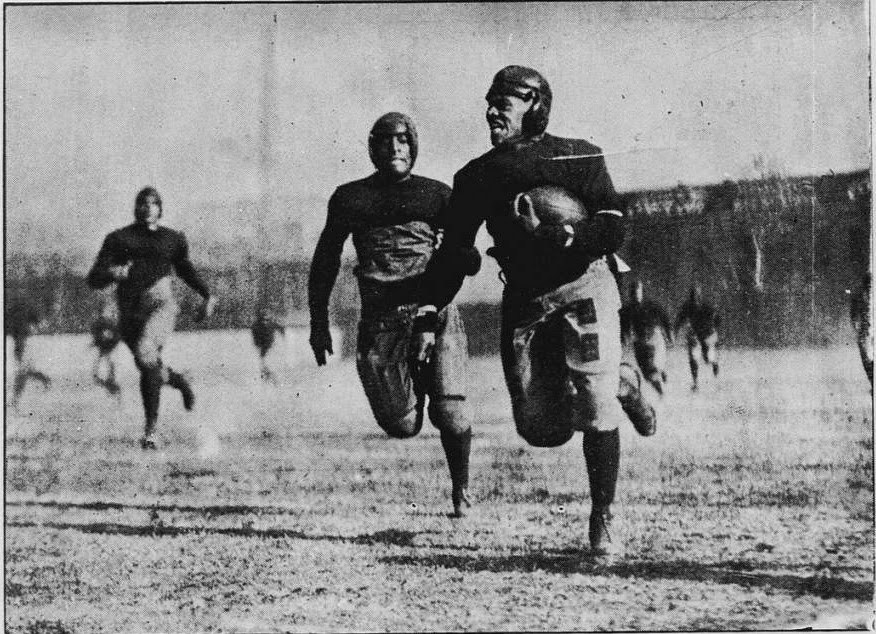

Whose fault is that? No one in particular. There isn’t any video of Byrd playing. There aren’t many more pictures. And stats from that era are very shaky. (Depending on who you believe, Byrd either ran for a 65 yard score or caught an 80 yard pass in 1922).

More than that though, Byrd and his contemporaries played in an era marked by discrimination most people alive today could not even comprehend. We all know that as late as the 60s and 70s, black players weren’t accepted at most colleges in The South, but in the 20s and 30s, even the NFL didn’t want black players.

Imagine how different pro football history would be if players like Walter Payton and Jerry Rice weren’t even allowed to play in the league? By all accounts, that’s the kind of talent we’re talking about with Jazz Byrd.

More than 20 years after his death, it’s time he got his due. Byrd should be inducted into the aforementioned halls of fame as soon as possible.

One thought on “The Black Red Grange: Black College Football’s Forgotten Legend”