The year was 1960.

Millions of Black Americans were still living under the oppression of Jim Crow, across the southeastern United States. Ninety-seven years after the Emancipation Proclamation and 95 years after the end of the Civil War, millions were restricted to using restrooms, water fountains and public schools based on a racial caste system built on white supremacy, and emboldened by weak federal laws that allowed them to remain in place.

Half a world a way, in Rome, Italy eight student-athletes from one black college, Tennessee State University, left their mark on the world’s biggest athletic stage.

Those TSU athletes, under the tutelage of now-legendary coach Ed Temple, came back to the Segregated South with seven gold medals, more than 78 of the 84 countries competing in the Rome Games.

|

| TSU track coach Ed Temple (Baltimore Afro photo) |

The most famous of them is Wilma Rudolph. If having to endure the indignities that came along with being a black woman in the south wasn’t enough, Rudolph, the 20th of 22 children, was also stricken with polio as a child. She managed to overcome the crippling disease and came away with three gold medals, including individual titles in the 100m and 200m as well as another gold as part of the all-TSU 4×100 team.

|

| (Baltimore Afro photo) |

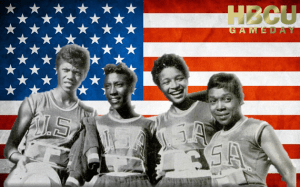

The quartet was part of Temple’s famed “Tigerbelles” a group that produced 40 Olympians from 1954 through 1960.

The relay team started with Barbara Hudson, a 4’10, powerfully-built Georgian that Temple had spotted at the Tuskegee relays as a high schooler. She passed the baton to another Georgian, Lucinda Williams. Next up was Barbara Jones, who was already in the record books as the youngest woman to win a medal at an Olympics when she won gold on the 4×100 squad at 15 years and 123 days in the 1952 Helsinki Games. And last, but certainly not least, was Rudolph, who had already run a world-record 11 seconds flat in the 100m earlier in Rome, but later had that time rescinded due to wind.

|

| (Baltimore Afro Photo) |

The group started off with a bang, running a world record 44.50 seconds in the preliminary heat before winning the gold with a 44.72 in the finals to beat the Soviets.

But when it was over, they returned back to the same old South. And much like fellow Olympian Cassius Clay (who would later become Muhammad Ali) that meant they were regulated to second place citizenship, despite their status as American heroes.

Lucinda Williams Adams, 56 years later, remembered the ugly realities she and her Tigerbelle teammates endured back then:

“We’d travel around the country and we couldn’t stop many places,” Adams told the Dayton Daily News. “We had to go to the bathroom in the bushes along the road and sometimes we slept in the car.

“I remember once we went into a restaurant in Baltimore. The owner chased us out, saying, “I don’t serve n––– here!’

“Stuff like that, I didn’t let it get me down. I made it motivate me.”

As black women in the Jim Crow South, these four Tennessee State University Tigers were reminded on a daily basis that they were not considered great or even equal by society. But 50 + years before the term was coined, the Tigerbelles showed in Rome that they were, indeed, Black Girl Magic.